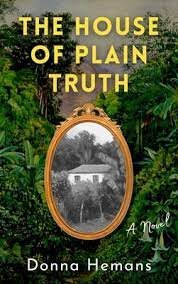

Donna Hemans, THE HOUSE OF PLAIN TRUTH: A Novel

Zibby Books author alert!! Zibby interviews award-winning author and repeat MDHTTRB guest Donna Hemans about THE HOUSE OF PLAIN TRUTH, a lush, evocative story about a fractured Jamaican family, a tapestry of family secrets that has been buried for decades, and a daughter determined to reclaim her home. Donna shares the personal history that inspired her novel—it involves her own family’s migration from Jamaica to Cuba and eventually to the United States. She also delves into her book’s themes of home, family, memory, identity, and the quest for belonging across generations and continents. Finally, she shares insights into her writing process, the journey of self-discovery through storytelling, and her current reading interests!

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Donna. Thank you so much for coming back on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books.” Last time, you were here for Tea by the Sea, a hundred years ago. Now you’re back as a Zibby Books author for The House of Plain Truth. Welcome.

Donna Hemans: Thanks for having me. It’s good to be back.

Zibby: I never would’ve imagined back when we first met at that — what was it? Ren Hen luncheon or something.

Donna: Right. Yeah, it was a luncheon.

Zibby: I was like, wow, she is such a good writer. This is amazing. Life has just unfolded in such a bizarre way. I had no plans to be a publisher. Here we are together. It’s great. Anyway, tell listeners, please, what The House of Plain Truth is about.

Donna: The House of Plain Truth is a story about family secrets which are triggered when Pearline decides to go back to Jamaica to help take care of her sick father. As he is on his deathbed, he asks her two things, one of which is to find her siblings who had been left behind in Cuba sixty years earlier. The second is to be his memory. Pearline has to figure out how those two things are connected.

Zibby: Interesting. Donna, how did you come up with the idea for this book? I know it has shifted a bit since we first read it and all that. When you first came up with the characters and the ideas and everything, what were you going for? What drove this whole process?

Donna: There’s a lot of Jamaicans who went to Cuba between 1900 and 1930, somewhere in that timeframe. My grandparents were among those who went to Cuba. As a child, I knew that, that they had lived in Cuba, that some of my uncles and aunts were born in Cuba before they came back to Jamaica, but I didn’t know anything at all about the story, exactly why my grandparents went, what their experiences were like in Cuba, and what made them decide to come back to Jamaica. That’s where this whole idea started. My grandparents died, my grandmother when I was sixteen and my grandfather when I was about nineteen or twenty. By the time I was of that age where I was really looking at and looking for family stories in a way that was much more than sitting around and talking, but getting that deeper connection and meaning, my grandparents were long gone. I couldn’t ask the questions that I would have asked as a twenty/thirty-year-old. I wanted to, in some ways, give them a story or at least to basically understand what their experience was like. That really drove this book. Then the second part of it was that my grandmother had a brother who went to Cuba and just never came back to Jamaica. I was trying to understand, what would that really be like to just no longer have that connection with a relative who, for all intents and purposes, just disappeared? There was a lot of that that came out in this book and in Pearline’s story.

Zibby: Interesting. Did you end up uncovering any more about your own family and any potential family lines in Cuba?

Donna: Not really the family lines in Cuba, no. I have got bits more. Once I start asking and probing, I get a little bit more information from my uncles and my father, but not much, nothing concrete because they were young. There’s so much that I think older generations just simply either didn’t talk about and didn’t give all the details that I would certainly ask or want to ask about today.

Zibby: It’s interesting that it came from your grandparents. Then Pearline is a grandmother herself in this book and has to wrestle with her family of origin, with her own children and grandchildren in the present day. As part of this whole sandwich generation — I hate that term, but I don’t know what else to say — when you have parents and kids and grandkids and you’re trying to care for everybody, Pearline does something which I thought was amazing. She’s like, you know what? I’m going. I’m going to go to Jamaica. You guys will be fine. I have to see my dad one last time. Tell me about that and that decision and where that all came from and what it feels like to be in that spot for her.

Donna: There may be two different things, or maybe even more. I think part of it is that so many immigrants from the Caribbean, and probably from everywhere else, moved to America or wherever they go with the idea that they’re going to work, and they’re going to go back and then have this lovely life in their home country. One of the things I’ve certainly seen with my uncles and aunts who have lived here for fifty years or however long is that there is no going back for them. Their friends have all moved on. There’s nobody in their hometowns. Where would they go? What would they do? Most people just simply don’t. I shouldn’t say most. A good number of people who wanted to go back just never end up going back. That the was first part of it. I wanted to write about somebody who went back home. I think, too, a lot of the stories that we read about migration, it’s usually the other way. It’s the person coming to America as opposed to the person going back home. I wanted to look at that story in somewhat of a different light. What was interesting, though, is that this part of it, this business about going back, came about around 2016. I was just writing something about a woman who went back to Jamaica. I had no idea who this person was. As I was writing it, I said, this feels like Pearline. This feels like this woman in this book I had been trying to write about for ten, fifteen years at that point. I had set the book aside. Once I got that piece with her actually going back to Jamaica, the story really fell into place. I just knew that’s where she needed to be. This is who was telling the story. This is how this book is going to work.

Zibby: Wow. Then it was off to the races. When you had that idea, tell me a little more about the process of bringing those sections together but also how you develop character and how you write and infuse your sentences with the beauty that they have and yet also maintain the plot and all that. What happened then? Take us through the play-by-play of what happened with the manuscript at that point.

Donna: At that point, I had had I don’t know how many versions. There are way more versions than I can count or even want to count of this book. At that point, once I figured out that Pearline had to tell her own story, I had to go back and figure out what needed to be in that story. What did she know? How could she tell it? One of the things that I wanted to do, certainly, was tell a portion of their family story that happened in Cuba. Pearline was three years old. There is only so much that she, one, truly could remember, and there is only so much that her parents probably would have talked about. Part of the process was just going back and culling through what I had, reshaping it, recasting it so that Pearline could tell the story, or she could tell what her father knew and become his memory, as he asked of her. It’s hard for me as a writer to go back and really look at and think through how everything works. Somehow, it really comes together. Sometimes it’s a lot of cutting and pasting and throwing things out. I have a little file called the sink. That’s where I drop everything, into the sink. Then I go back, and I move it back into the document. It’s a lot of that, just moving it back and forth and figuring out what really fits and where and if it doesn’t fit, figuring out if it will fit in something else as opposed to getting rid of it altogether.

Zibby: I’m like, this paragraph is so great. Where can I put this?

Donna: Where can I put it? I kind of worry that when I move things like that, I might end up writing a completely different book and lifting something that I forgot that I put into another book. In case anybody hears the same thing somewhere else, this is what happened.

Zibby: You can’t really plagiarize yourself, right?

Donna: There is that. I hope not.

Zibby: I hope not. We’ll find out. Part of this book really examines what home even means, home to Pearline in Brooklyn, home in Jamaica, what it means to come home, her father’s sense of home, going back home, as you say. Talk a little bit about that and how everyone defines home and where you see the role of that in this book.

Donna: It’s one of those things that I think I’m trying to define for myself. Where is home? As somebody who has lived in Jamaica, who has lived here, in two different countries, there really is a sense of, where do you belong? There are some times when I go back to Jamaica and I feel like I have no idea what’s happening or why we do things a certain way. Then there are times when I’m here, and I’m asking the same question. There are lots of little things that we don’t often think about in our day-to-day that really define home. I think that’s what Pearline finds when she goes back to Jamaica. There is so much that her sisters have accepted and that they do. There is this house that they have all lived in. That is home to her, but her sisters don’t necessarily have the same kind of interest in holding onto this house. Is that home? Is it this physical place? If you get rid of this place that you’ve known, does that mean that you no longer have a home? Have you lost it? That is part of it.

The other part, for Pearline, because her family has been in multiple places, in Cuba, back in Jamaica, and then she in New York, a lot of it really comes back to wanting this place that is always hers and which nobody can tell her, you have to go. This is ours. No matter who you are in a family, no matter what it is that you have done, there is this place that will always welcome you. That’s what Pearline wants. That’s what she thinks her parents had wanted. I think that’s what all of us really want. There is this place, whether it’s the family members, your parents or your siblings or some other friend who you have found who you consider family, who will always welcome you. I think, in some ways, that’s what Pearline is searching for. That’s what she wants. She’s fighting with her sisters, in some ways, for them to understand that it’s not just a place. It’s not just an old house.

Zibby: Yes, oh, my gosh. I love how you wrote about the sisters. It’s so hard to characterize those intimate family relationships and the fights that you get and all of that. How you depicted three women of a certain age still kind of getting into it — I was breaking up a fight with my kids this morning. The idea that they’ll be going through this for decades is like, oh, my gosh, seriously? Yet here you have these sisters who are, not in the same way — I hope it wasn’t about watching a YouTube video or something — still bickering and having differences of opinion. Then who is left to moderate that? When there’s no one left to sort of referee, how do these big conflicts get resolved? It’s such an interesting question.

Donna: Yeah, it is. They’re adults now. They have to resolve it. The funny thing — I was talking to one of my nieces the other day. She is twenty-one. She is now the adult. She is the one who has to begin to start looking at and figuring out how to take care of — she’s twenty-one. It’s just this interesting way of looking at life. Somebody has to be the one in charge at some point. I don’t want to start thinking that it’s time to set aside everything and give it over to somebody else, but it’s a part of life. That’s where it is. The parents are gone in this case. The children are not necessarily there yet to — Pearline’s daughter is still in Brooklyn at that point. She’s not there to step in to try to help to solve that crisis. The sisters have to do it themselves. If it had continued in some way, it got bigger, hopefully, the children would’ve been able to step in, but who knows? Maybe not. Some fights, you don’t want to get into.

Zibby: That’s true. Actually, I probably shouldn’t even be refereeing at this age anyway. I feel like that’s the parenting advice. Let your kids sort it out. I’m really bad at that. Donna, tell me about more of your life story. When did you leave Jamaica? What happened? You were born, and then what happened?

Donna: I was born. I grew up in Jamaica. I left when I was sixteen. I finished high school. My parents came here in the sixties, went to college here. My oldest sister was born here. Then they went back to Jamaica. I think it was just one of those things where, well, we have one child who is going back to America to finish her college education. We have these two other children. What do we do with them? I think a lot of it was probably more of that kind of a story. I finished high school, came here, went to college, and just stayed.

Zibby: You’re so dismissive of it. It’s an interesting story. There are probably eight thousand stories in that story.

Donna: There probably are.

Zibby: I know you said you look at things in Jamaica and then you look at things here critically, and neither system is really perfect. How did you feel then? Do you feel much more of a sense of belonging to either place now? Did you feel like you belonged to Jamaica when you lived in Jamaica when your family had been in the United States? How has that shifted over time for you?

Donna: I think it fluctuates. When I’m in Jamaica, I feel like this is exactly where I need to be and where I belong. Then I maybe go to the bank and try to do some business, and I realize, okay, there are ways to do things better. Then I come back here. Everything feels like, okay, this is where I need to be. It depends. It depends on where I am and what it is that I need. I think what I have decided or have figured out is that wherever I am at that moment is where I need to be. I don’t know that I have any other answer for that or any other way to —

Zibby: — No, that’s perfect because that’s the whole Zen goal, isn’t it? Be where your feet are and all that. There you go. You already crushed it.

Donna: Without even knowing it.

Zibby: Without even knowing it. Zen master Donna. When did writing come into the picture?

Donna: I think it was always there in some ways. I know definitely in high school, I would enter any competition that they had, any writing competition. Then in undergrad, I had this grand idea that I was going to be a lawyer. I was going to go out and save all the people who needed to be saved from everybody else. That was a plan. I went in thinking, all right, let me just major in English because that’s a good foundation for this law career I was going to have. Took a creative writing class. Added journalism as my dual major. Took a creative writing class. I liked it, so I started writing. Wrote some more and once I graduated, started working in journalism. Then I started writing what was my first book, River Woman. I realized that I knew I had a story. I didn’t know exactly how to write this book or how to tell this story. Decided, okay, it’s time to leave New York and go to grad school so I can write this book. That is pretty much how I started writing, how I got here.

Zibby: Not everybody who realizes they have a story decides to go to grad school. That’s a conscious, obviously, choice. Why did you decide to do it? Do you feel like you learned certain things there that have really helped you? Was it the community? Was it a little of everything?

Donna: I think it’s a little of everything. The community, mostly. I was around journalists. They were interested in a completely different kind of story. While it served its purposes, it was not what I wanted to do or needed in order to write this novel. The thing that I got most out of a creative writing program was not so much about learning how to write, but more about learning how to read. I had to be able to step away from the book, read it, understand it, but step away from it or pull myself away from it in order to revise it. I think that you need to be able to read and read critically or read in a different way. In high school and stuff, when you read literature, they’re talking about theme. What did the writer mean? All of that sort of stuff. It doesn’t necessarily help you when you’re trying to write because if you are thinking too much about theme, you’re not thinking about plot. You’re not thinking about your characters. I think I needed that graduate program to be able to read other people’s work and by doing that, figure out and understand how to read my own work critically. Without that experience, I don’t know where I would be. I’m sure I would be writing still, but I don’t know that I would be here in this place.

Zibby: On this Zoom right now.

Donna: On Zoom. Who knows? I might be. I don’t know. I might have gone on and become a lawyer. I don’t know.

Zibby: For listeners who aren’t familiar with your previous works, can you talk about the River Woman and Tea by the Sea?

Donna: River Woman is set in Jamaica. It’s about a woman who is about to migrate, and her son drowns. It really is about how she and the community deal with the death of this child. I’ve been trying to not kill people in the books that I write, but that hasn’t happened yet. Tea by the Sea is about a young woman whose child is taken from her at birth. She spends seventeen years looking for her daughter. We know at the outset of the story that the father has taken the child. It really is just her trying to find the father and trying to understand why he took her child. Her hope is to develop a relationship with her daughter.

Zibby: Have you read The Leftover Woman by Jean Kwok? It just came out recently.

Donna: No, I haven’t.

Zibby: It’s different but similar themes, the search for family and giving up a child and all of that. You might like it. Your book recommendation of the day, there you go. Are you working on anything now?

Donna: I am. One of the benefits of having all these projects that you set aside is that I can always go back in and pull one out of the drawer and work on it. The book I’m working on now is another one. It’s actually the second book I started writing and for some reason, just couldn’t quite figure out how to tell the story as well as I wanted to tell it. Now I think I have finally figured it out. I am hoping to finish it up soon.

Zibby: Exciting. Better that you take it out of the drawer than taking it out of the sink, right? Is that better?

Donna: Well, I like both. The drawer is

Zibby: From the Drawer and the Sink could be a blog or something. Do you know what I mean?

Donna: It could be, yeah.

Zibby: It would be fun to do some sort of Twitter account where people just put sentences that they haven’t found a place for but that are great sentences. That’s a great sentence. What a fabulous first line of a novel.

Donna: I can’t use that. What about you?

Zibby: Exactly. Here, take it. What do you like to read in your spare time?

Donna: Lately, I’ve been reading just a lot of Caribbean fiction because I have embarked on a project to fully try to understand a little bit more about Caribbean literature. It has been fun. The last book I read was The Book of Lost Saints. I can’t remember the name of the author right now because I don’t remember names. It was a really interesting book. I highly recommend it. He pulled in a lot of ghosts in order to pull together a modern-day story about what happened during the Cuban Revolution. It was a really fascinating, interesting book.

Zibby: Amazing. What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

Donna: I would say to read and read and read a lot and also to not give up on your stories. There are times, yes, when you may have to set something aside, but I think coming back to it when you’re either in a different place or you have really been able to look at and think about it in a different way can be helpful. I think it helps. I have heard a lot of people say, oh, no, that’s dead. I will never look at it again. I think sometimes you can take that time, step away from it, and still find the beauty in it and figure out how to retell the story in a way that works.

Zibby: I love it. Is there anything from Jamaica that you miss in particular, a food, a smell, a place, something that you’re like, if only I could just have that be here…?

Donna: The beach is one. We have, we call them otaheiti apples. I can’t remember, there’s another name for it. It’s a little red apple, fully white inside. It’s just absolutely delicious. The last few times I went, it was out of season, so I haven’t had any. I have figured out how to time my trips in order to get there for certain fruits, but not always.

Zibby: Wow, that’s amazing. The airlines should maybe do a better ad campaign.

Donna: They should, actually. That’s not a bad idea.

Zibby: Not a bad idea. Donna, congratulations. Thank you. I’m so excited to be a small part of the journey of bringing this beautiful story into the world. The House of Plain Truth. Congratulations.

Donna: Thank you.

Zibby: Yay, more to come. Thank you so much. Bye, Donna.

THE HOUSE OF PLAIN TRUTH: A Novel by Donna Hemans

Purchase your copy on Bookshop!

Share, rate, & review the podcast, and follow Zibby on Instagram @zibbyowens